Powerful First Nations Art Exhibit Comes to PAMA in Brampton

Published August 4, 2017 at 8:06 pm

As many people in Brampton know, one doesn’t have to travel far to find powerful art exhibitis.

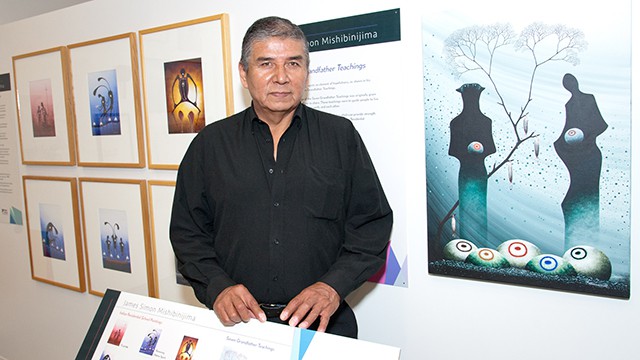

As many people in Brampton know, one doesn’t have to travel far to find powerful art exhibitis. Right now, PAMA is home to some incredible work by First Nations artist James Simon Mishibinijima, work that’s currently featured in the Peel 150: Stories of Canada exhibition (On now until Oct. 15).

Born in 1954 in on Manitoulin Island, James Simon Mishibinijima grew up in Wikwemikong, one of the few Unceded Territories in Canada. Never the subject of a treaty, Wikwemikong has been able to preserve some of its pre-Columbian First Nations characteristics.

Mishibinijima means “Birchbark Silver Shield.” As a boy, Mishibinijima was given the name James Alexander Simon by missionaries who found his name difficult to pronounce. His path as an artist was set early on as he was growing up in Wikwemikong. In some ways he feels that his destiny in art found him, pulling him in an unexpected direction away from an inclination to become an RCMP officer and toward a life as a professional artist.

Among his early teachers was Francis Kagige, an artist and neighbour, and recognized as one of the important pioneers of Wikwemikong art. Kagige had one of the few painting studios in the community. Mishibinijima would frequently visit his elder there where he was given his earliest instructions in painting and some lessons about style. Kagige also shared teachings about their Ojibwe culture and told the young artist his stories. The community’s elders and Mishibinijima’s relatives also imparted oral histories and described the myths and legends that are part of his cultural heritage.

Over the course of his career, he developed two signature styles. One is known as his “mountain paintings.” A dominant characteristic of these paintings is the blending of the land and the human elements to create images of energies that the land generously provides to all who seek it as sustenance.

A second personal style adapts the style of ancient pictographic paintings. Just as the painted petroglyphs make use of mysterious visual symbolism referencing human forms and translating radiant energies in pictorial terms, so Mishibinijima found in their spare human-like symbols potent signs with which to set down his, his family’s, and his community’s stories.

The paintings comprising the current exhibition at PAMA entitled “Indian Residential School Paintings” tell – illustrate – Mishibinijima’s mother’s stories as she gave them to him and as they revealed themselves to him in dreams. Her stories are depicted as pictographs.

They recount her experiences when, as a young Ojibwe woman, she was a student in the middle years of the twentieth century at the Spanish Indian Residential School situated on the northern banks of Georgian Bay.

Mishibinijima’s mother passed on her stories to him later in her adult life, over the course of perhaps a decade and a half. By giving her stories to her son, she exhorted him to “paint them.” By sharing such shocking details from her life as a young adult, it was her hope that the truths of “what happened” would live on into the future, beyond her own life.

The paintings’ deceptively simple style provides the maximum opportunities for someone experiencing his paintings, particularly children and young adults, to reflect on this tragic chapter in our nation’s history and to understand the pain and trauma that people their own age experienced. His paintings are intended to open dialogues about personal and community values, and about the need to confront the truth.

Article courtesy of Thomas Smart, PAMA art gallery curator.

insauga's Editorial Standards and Policies advertising